This journal is meant to be an experiment in progress, a reading ground, bringing together people with many different backgrounds, any faith or no faith, but sharing a common need to “think out of the box” and engage in constructive dialogues at the intersection between scientific and philosophical inquiries and society. A good article is like a good bottle of wine: with age it can only get better. It is thus that any interested reader is welcome to submit her/his original articles, even if they were already published elsewhere (articles submission) or recommend articles or books written by others, even a long time ago (articles recommendation). All articles are welcome on the following general topics of :

(i) philosophy and religion;

(ii) science and evolution;

(iii) policy and society.

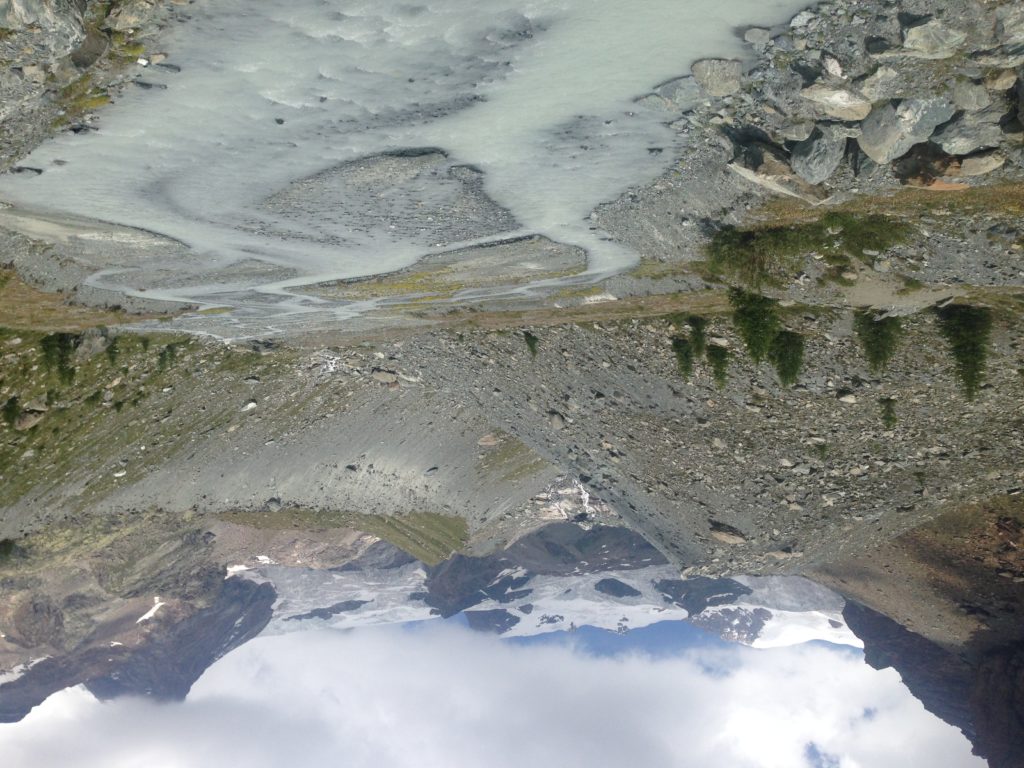

The magic mountain

People taking different mountain trails can meet at the top. However, there are many possible mountains and those climbing one remain separate from those climbing others. There are also many who do not like to climb mountains and prefer instead to go down to the sea, or stay in the city or the countryside. It remains true, however, that we all move on the same ground and under the same sky. We all started in the womb of our mothers, we all eat and sleep. Most of us grow up, learn, love and reproduce. Many become old, we all die. It is thus that, coming from many places and going in different directions, we eventually converge.

Science Philosophy and Life’s decisions

There are two disciplines in the world that have been traditionally called to understand and nurture life, prevent and cure disease, and give “hope beyond all hopes”: science and religion, which at the beginning were both called philosophy. Closely intertwined with them are nature and policy. Irrespective of any faith or belief, solid cross-communication should be established among principles and discoveries of scientific inquiry and philosophical, moral and legal guidelines, offering a framework for life’s key decisions, at the personal and societal level.

To our knowledge, a forum for such exchange of information and view points is missing, due to the explosion and increasing specialisation and fragmentation of knowledge and thoughts in any individual field.

In the beginning of human history, the tasks of scientists, physicians and philosophers coincided. They were expected to provide knowledge and guidance to orient society, heal the afflicted and accompany them in the “afterlife”. Today, the task of the physician comes before that of the priest or the philosopher, and can take their place entirely. On the other hand, the policy maker, philosopher or religious leader have rare and cursory consultations with the scientist.

What is the correct use of scientific information for guidance and disclosure to the public ? What is the appreciation of scientific research and how scientific progress is made by those in the medical profession ?

Psychologists and psychiatrists aspire to take the place of philosophers and theologians in tackling not only human anxiety in the ever-increasing uncertainty of daily life but in answering the “ultimate” questions of meaning and significance. What is the appreciation by psychologists and psychiatrists of the ontological dimension, to which have pointed philosophy and religion throughout history, in their various forms ?

Is the scientist’s and physician’s knowledge of the human body and its cells at odds with the “concepts” of a philosopher or a “belief” of a theologian? Is the human mind as studied by the psychologist a sufficient substitute for the foundation of being, as sought by the philosopher? Are the questions of life and its unavoidable dissolution a private matter for individuals and their families or an existential challenge for all of society? What role do socioeconomic and cultural factors, as well as inequality, play in this story?

All societies struggle with life and death decisions, all have an impact and are impacted by their environment. We hypothesize that the human condition can best be addressed through an integrated interdisciplinary approach that combines the exponential increase of scientific knowledge with the wisdom accumulated by philosophers and theologians over the millennia.

Medicine and Religion

The man who plays chess with death is the unforgettable image and symbol with which the Seventh Seal of Bergman begins. The survival instinct inherent in every organism culminates in the mind of man, engaged in a game that he cannot win, with the only hope of postponing defeat. Man alone can do no more. But it is precisely from the abyss into which he sinks that he can hear a voice calling him, offering him help and, if he wishes, carrying him up.

At the beginning of history there was no distinction between medicine and religion and even now they have the common purpose of giving strength and hope of life. Both aim to protect health. The Latin “salus”, similar to “salvus”, means salvation, safety, integrity. The English equivalent, “health”, has a common etymology with “whole”. Medicine and religion are both called to support the integrity of the human person, an indivisible unity of body and spirit in harmony with the universe. When this integrity is broken, illness and death take over. When this integrity is sustained and sublimated, it becomes light. It is on Mount Tabor that Peter, James and John saw Jesus shining more than the light and it is down again that they asked themselves “what does it mean to rise again from the dead ? (Mk 9:10)”.

The spirit of man unites intellect and will and is the basis and spring of action. The spiritus of the Latins, pneuma of the Greeks, is above all breath, without which every animated being ceases to live. The pneuma was for Anaximene the universal element from which all the other elements originated. This same pneuma for philosophers like Prassagora and Erasistratus was air that enters the arteries and veins and, circulating everywhere, keeps alive. Even today it could be said that when the newborn child reels and takes in air, it is the spirit of Being that enters into its lungs and dilates them.

Today’s medicine is firmly rooted in knowledge of the vital processes of the human organism, made up of molecules, cells, tissues and organs and the mechanisms that connect them. The enormous successes to which we have arrived are the result of the reductionistic and mechanistic thinking of the modern age and the rigorous experimental research to which they have led. It is thanks to this approach that diseases like plague and leprosy are mostly problems of the past. Neurology and surgery have made great strides and it is recently in the news that a totally paralysed person has regained the ability to move the limbs thanks to a microchip implanted in the brain able to read the will.

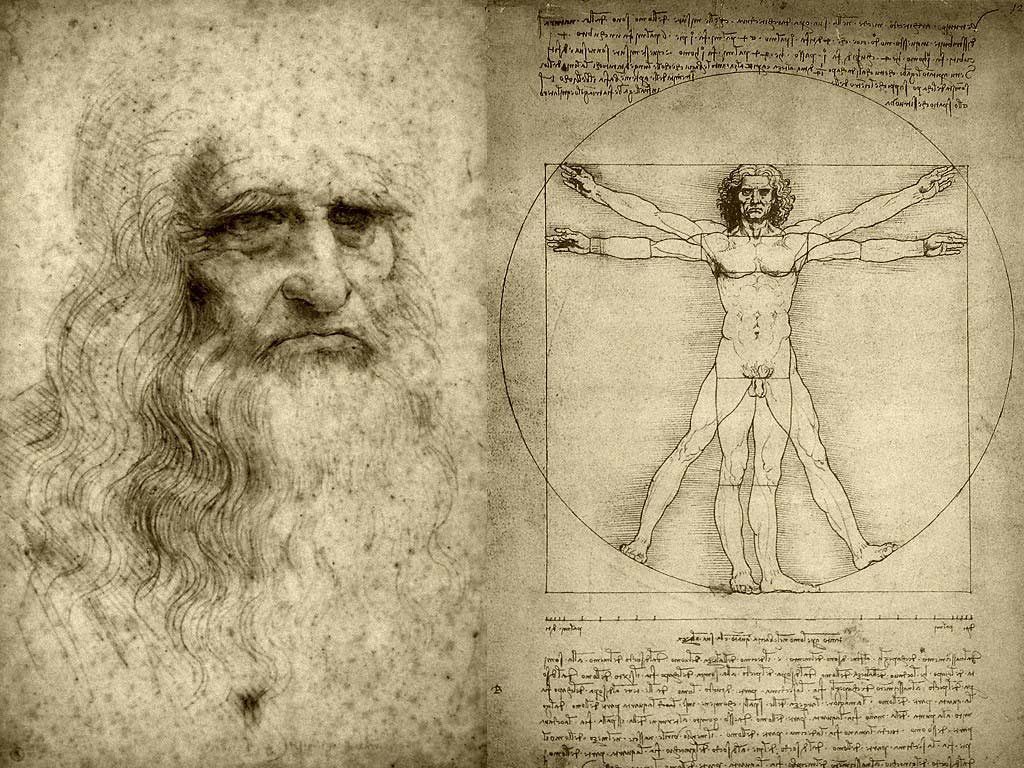

All of this gives great hope for the future, but it also frightens, as it can frighten the fact of reducing man to a machine that can be brought into repair and that, if it does not work anymore, it can be scrapped. Faced with these serious possibilities, it is important to remember that the immense effort to understand in the smallest details of “how man is made and works” finds its origins in Christian humanism and in its anxiety and love for the whole man. With many centuries of history behind it, next to the dissections of Leonardo’s human body are his great pictorial works. The enigmatic design of the man with his arms and legs stretched out in the middle of a large circle reverberates in the smile of Mona Lisa.

With man at the center, very often it was thought that God could be put aside. But where is God if not in the heart of man, very concrete heart of individual men, women, old people and children? Even now, as at its beginning, modern medicine finds its reason and fulfilment in going towards those in need. With the modern effort to reach more and more personalised forms of treatments, it is always important to go towards the heart of man in which one may find God.